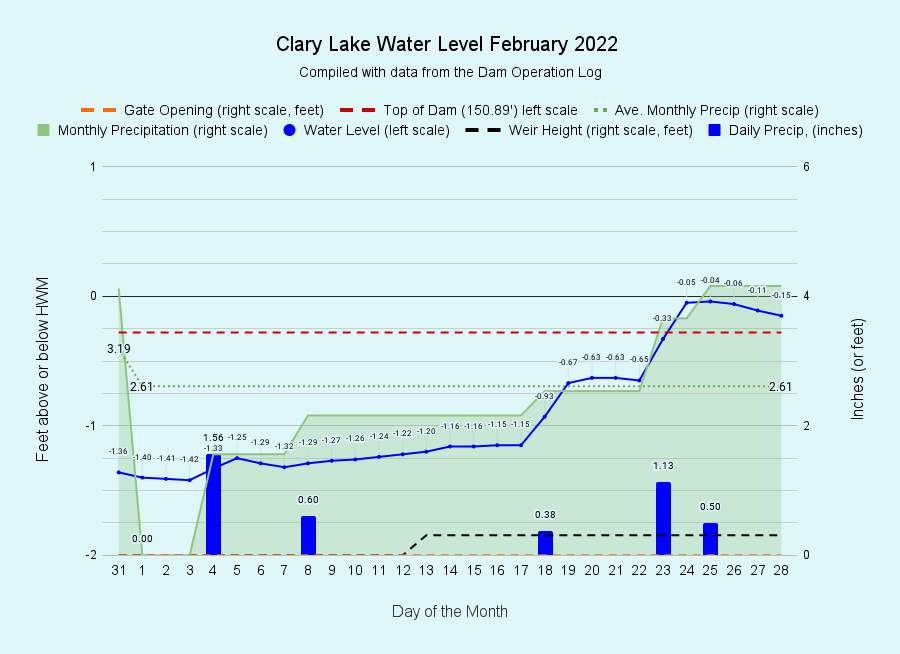

I have archived the February 2022 Water Level Chart (at left). The above-average precipitation with which we started the year (January ended 0.93″ above normal) has continued throughout the month of February which saw a total of 4.16″ of precipitation (water), the effect of which has been to put us fully 2.48″ above normal for the year to date. This bodes well for ground water supplies this spring, in marked contrast to the last 3 or 4 years. We’ll have to wait and see if the cycle of summer drought has been broken. All the rain and snow we received in February resulted in the lake level rising to unseasonably HIGH levels, overtopping the dam on February 23rd and coming to within half an inch of the HWM on the 25th.

Today, on the last day of February, the lake level has receded but there is still a little water flowing over the dam which will continue for a few more days before receding below the top of the dam (150.89 feet). Our general goal in late winter is to start raising the lake level in anticipation of meeting increased minimum flows in mid-March, so while the high water did come as a surprise, it wasn’t wholly unwelcome. We’ll let the lake level fall to around -1 foot or so over the next few weeks as we head into Spring.

Today, on the last day of February, the lake level has receded but there is still a little water flowing over the dam which will continue for a few more days before receding below the top of the dam (150.89 feet). Our general goal in late winter is to start raising the lake level in anticipation of meeting increased minimum flows in mid-March, so while the high water did come as a surprise, it wasn’t wholly unwelcome. We’ll let the lake level fall to around -1 foot or so over the next few weeks as we head into Spring.

While high water like we’ve seen this winter is somewhat unusual given our current water level regime under the Water Level Order, historically high winter water levels have been the norm not the exception, the evidence of which is particularly evident around the lake in the form of “ice berms” or “ridges” which are sections of shoreline that over many decades have been slowly but inexorably bulldozed up by expanding lake ice. You’ve all seen these raised berms around the lake. The picture at left shows a pronounced berm 2 to 3 feet tall in front of Eleanor Goldberg’s camp at the end of Hornpout Lane. Similar berms can be found all along the western and southern shore of the lake and along other, isolated sections of shore where there was a large enough expanse of ice acting against the shore, and where the lay of the land offered some resistance to the pressure of the expanding ice. I’m aware of one berm that is close to 7 feet tall and all but hides the small camp that sits behind it.

While high water like we’ve seen this winter is somewhat unusual given our current water level regime under the Water Level Order, historically high winter water levels have been the norm not the exception, the evidence of which is particularly evident around the lake in the form of “ice berms” or “ridges” which are sections of shoreline that over many decades have been slowly but inexorably bulldozed up by expanding lake ice. You’ve all seen these raised berms around the lake. The picture at left shows a pronounced berm 2 to 3 feet tall in front of Eleanor Goldberg’s camp at the end of Hornpout Lane. Similar berms can be found all along the western and southern shore of the lake and along other, isolated sections of shore where there was a large enough expanse of ice acting against the shore, and where the lay of the land offered some resistance to the pressure of the expanding ice. I’m aware of one berm that is close to 7 feet tall and all but hides the small camp that sits behind it.

We’re all aware that water expands when it freezes and forms ice (which is why ice floats). That expansion can exert considerable pressure on any vessel attempting to contain the freezing water (think “burst pipes”). Well think of the lake shoreline as a vessel tasked with containing the lake and realize that the expanding ice exerts pressure on the shore line in the same manner as it does in the water pipes in your cellar. It is easy then to envision the forces at work in the formation of ice berms on the shore. These are the same forces that cause pressure ridges in the ice and like ice berms, they primarily occur where there is a large expanse (or “fetch”) of ice to provide some real expansion potential! A mile wide expanse of ice will expand more than a half mile wide expanse of ice. I took the above picture of a pressure ridge February 13, 2021 by the outlet of Clary Lake. This one was close to 3′ tall and it would be pretty exciting to hit one of those on a snowmobile at speed! I’ve also seen these ice ridges buckle down instead of up, then they fill with water and skim over making a serious hazard for unsuspecting skaters or snowmobilers. Anyone who’s spent time on Clary in the winter knows that pressure ridges often form up at the northwest end of the lake, and to a lesser extent (for some reason I’m not aware of) at the southeast end.

We’re all aware that water expands when it freezes and forms ice (which is why ice floats). That expansion can exert considerable pressure on any vessel attempting to contain the freezing water (think “burst pipes”). Well think of the lake shoreline as a vessel tasked with containing the lake and realize that the expanding ice exerts pressure on the shore line in the same manner as it does in the water pipes in your cellar. It is easy then to envision the forces at work in the formation of ice berms on the shore. These are the same forces that cause pressure ridges in the ice and like ice berms, they primarily occur where there is a large expanse (or “fetch”) of ice to provide some real expansion potential! A mile wide expanse of ice will expand more than a half mile wide expanse of ice. I took the above picture of a pressure ridge February 13, 2021 by the outlet of Clary Lake. This one was close to 3′ tall and it would be pretty exciting to hit one of those on a snowmobile at speed! I’ve also seen these ice ridges buckle down instead of up, then they fill with water and skim over making a serious hazard for unsuspecting skaters or snowmobilers. Anyone who’s spent time on Clary in the winter knows that pressure ridges often form up at the northwest end of the lake, and to a lesser extent (for some reason I’m not aware of) at the southeast end.